State of the Nations: lessons in tackling child poverty from across the UK

Child poverty has been rising across the UK over the past decade, driven by large cuts to the social security system. But some divergence in the numbers will arise between the four nations because of policy choices. What are the key differences in how child poverty is tackled in England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland? What can we learn from progress being made? And as the new UK government creates its child poverty strategy, what path should it take?

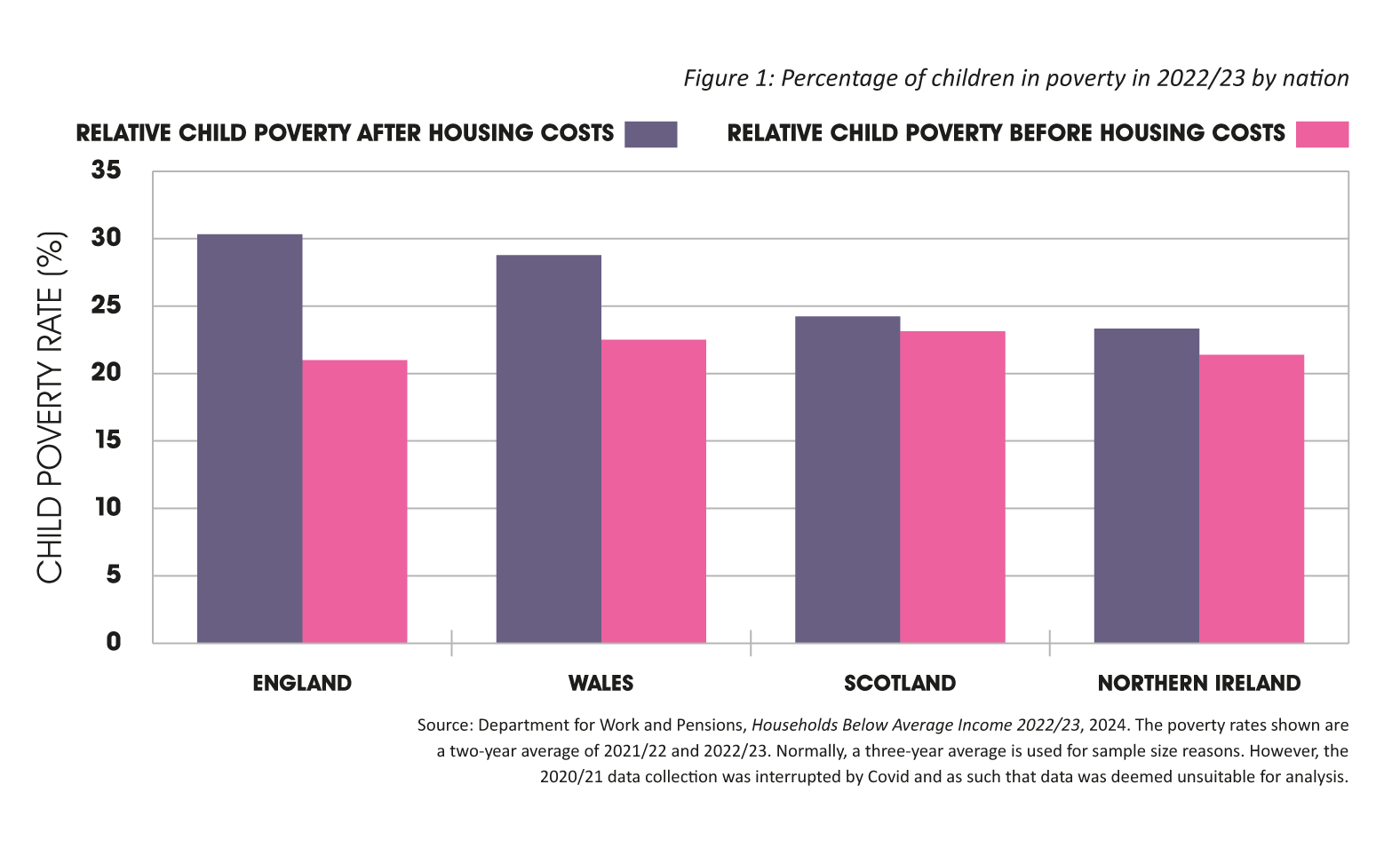

The overall child poverty rate in the UK is 30 per cent after housing costs are taken into account, but the picture in the four nations of the UK varies. Figure 1 shows the percentage of children in poverty in 2022/23 (the latest data available) across England, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland both before and after housing costs. We can see that the after housing costs (AHC) poverty rates in England and Wales are higher than in Scotland and Northern Ireland, but the before housing costs (BHC) rates are very similar. This indicates that higher housing costs in England and Wales are a key reason for higher poverty rates in those nations. We can also see that AHC poverty is higher than BHC poverty in all nations. This is because low‐income households spend a high proportion of their income on housing. CPAG uses the AHC measure as the headline child poverty figure because this gives a better picture of how families are doing, given housing costs are not discretionary – people have to pay the rent.

Figure 1: Percentage of children in poverty in 2022/23 by nation

For accessible figures, please see GOV.UK

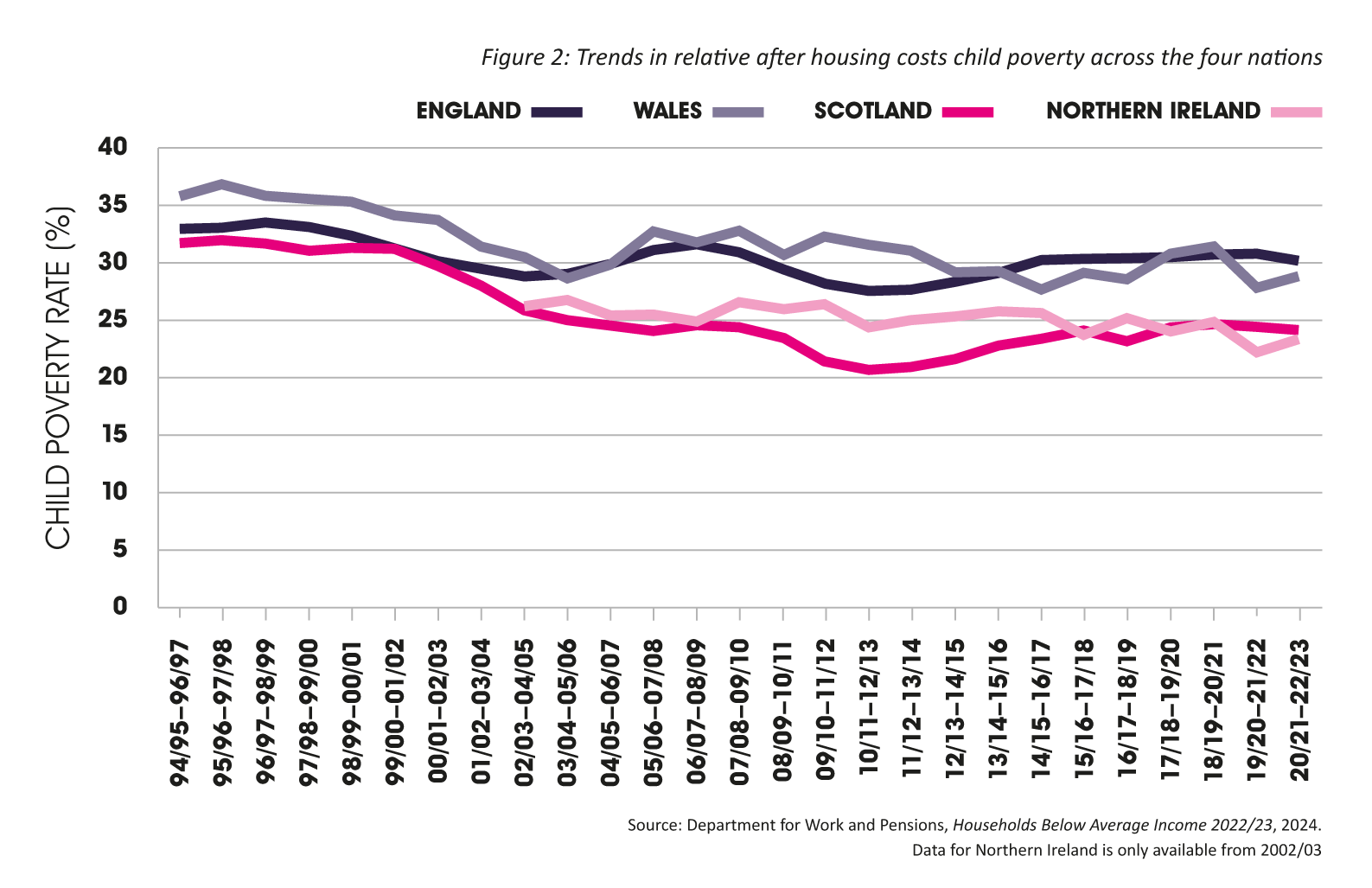

Trends over time can tell us more about the driving factors behind child poverty. Figure 2 shows that trends in child poverty AHC across the four nations broadly follow the same pattern. Child poverty was greater than 30 per cent in England, Wales and Scotland in the 1990s, before falling in the first half of the 2000s. There was then a plateau, before poverty fell again in the latter half of the 2000s. In the 2010s, poverty rose or stayed flat across the four nations. The fact that poverty across the four nations followed similar trends is unsurprising: for most of this period, devolved administrations had little power over the policy levers which directly affect household income and therefore poverty.

Figure 2: Trends in relative after housing costs child poverty across the four nations

For accessible figures, please see GOV.UK

The key factor behind the UK trends is the change in the adequacy of social security. Since 2010/11, child poverty has risen, primarily because of cuts to social security. The UK government now spends £50 billion a year less on social security than it would have spent if cuts, freezes and other changes since 2010 hadn’t happened.1 Households with children have borne the brunt of these cuts, with regressive policies like the two‐child limit and the benefit cap almost exclusively affecting families with children. These trends show how critical investment in social security is, if we are to begin to reduce child poverty levels across the four nations.

While the two‐child limit remains in place, child poverty will continue to rise across most of the UK. The new UK government is working on a child poverty strategy, but without knowing what’s in it yet, we can’t assess what the poverty effect will be. Table 1 shows what we might expect to see happening to child poverty across England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland over the next five years.

In England, Wales and Northern Ireland, there are currently no targeted policies in place which would substantially reduce child poverty, therefore we would expect poverty rates to rise slightly. In Scotland, we expect to see a historic reduction in child poverty due to the Scottish child payment, a £26.70 a week payment to children aged under 16 in families receiving universal credit. However, if the level of the payment is not uprated in real terms over time and the two‐child limit remains in place, child poverty will then start to rise again, albeit from a much lower base.

Table 1: Forecast impact on child poverty over the next five years

| Overall effect | Largest driver of rising poverty | Largest driver of falling poverty | |

|---|---|---|---|

| UK | Slight rise | Two-child limit | Possible impact of a UK child poverty strategy (unknown) |

| England | Slight rise | Two-child limit | Possible impact of a UK child poverty strategy (unknown) |

| Scotland | Large fall | Two-child limit | Scottish child payment (result of Scotland child poverty strategy) |

| Wales | Slight rise | Two-child limit | Possible impacts of Wales/UK child poverty strategies (unknown) |

| Northern Ireland | Slight rise | Two-child limit | Possible impacts of NI/UK child poverty strategies (unknown) |

Note: These results are based on UKMOD version B1.12. UKMOD is maintained, developed and managed by the Centre for Microsimulation and Policy Analysis (CeMPA) at the University of Essex. The results and their interpretation are the author’s sole responsibility.

The relative child poverty measure: A child is living in poverty if they live in a household with income below 60 per cent of the national average (median) income, adjusted for household size.

What are the nations doing differently?

Scotland

The Scottish government introduced income targets for child poverty reduction into legislation under the Child Poverty (Scotland) Act 2017, which was passed with cross‐party support. The Act mandates interim and final targets for child poverty, with child poverty AHC to reach 18 and 10 per cent respectively. These targets have been instrumental in securing political commitment and resources to tackling child poverty in Scotland. The government also introduced a poverty and inequality commission, and child poverty delivery plans. Importantly, some social security powers have also been devolved to the Scottish government, with Social Security Scotland delivering some benefits and taking a human rights approach to that delivery. The Scottish government also mitigates the benefit cap as far as possible within its devolved powers.

CPAG’s modelling suggests that the Scottish child payment will reduce child poverty by 5 percentage points. A series of other, smaller policies including Best Start grant and Best Start foods will reduce child poverty by 1 percentage point. Because of a lag in the data, we do not yet know if the interim target of 18 per cent has been met, but it is clear that far more needs to be done to meet the 2030 child poverty target of 10 per cent.

‘Social security support is helpful but even still I really find money is tight and hard to manage finances. I receive the Scottish child payment which I am very grateful for but I am struggling to get by with high costs. My children get free lunches [as part of Scotland’s universal free school meals being rolled out for primary pupils] which helps reduce some of my stress about feeding my children during the day. It’s good to know they have a warm meal. After summer holidays, I get £100 each for my children’s uniform – of course I am really grateful for this but my children are young and growing and this doesn’t stretch for their uniforms for the year.’

Nanda, single mother to two young children who works part time, participant in Changing Realities (a collaboration between parents and carers, academics at the University of York and CPAG)

Wales

The Welsh government recently published a child poverty strategy2 as part of its requirement under the Children and Families (Wales) Measure 2010 to set child poverty objectives and to report every three years on progress towards them. However, in contrast to Scotland, this Welsh strategy has no targets for child poverty reduction. It is also not clear how the strategy will translate into tangible actions and how or when they would be delivered, making it more difficult for the government to be held to account.3

Wales does have fewer devolved powers than Scotland, and has made some progress such as on expanding free school meals, but much more needs to be done to address family income if we are to see a reduction in child poverty in Wales. In the absence of new poverty reduction policies, life is going to remain difficult for children in poverty.

‘Social security support available in Wales is extremely limited. There is access to free school meals for all primary age children being rolled out across the whole of Wales starting with the youngest learners. The process needs to include all school age children. Children don’t stop suffering from hunger due to getting older, my 14‐year‐old son regularly shares his [means‐tested] free school meal with his friend whose family don’t meet the criteria for free school meals but are struggling financially so their son often has no lunch and is hungry.

‘Wales also provides a school essentials grant; this is £125 per learner per school year from reception to year 11... Children going into year 7 now receive £200 due to the increased cost associated with starting secondary school. This is helpful to a degree but due to secondary schools insisting on such specific uniforms with embroidered badges the grant isn’t sufficient.’

Kim, mother to four sons, living with a disability, participant in Changing Realities

Northern Ireland

The Northern Ireland Act 1998 requires the Executive to ‘adopt a strategy setting out how it proposes to tackle poverty, social exclusion and patterns of deprivation based on objective need.’ The last child poverty strategy, covering 2016 to 2022, had two overarching aims of reducing the number of children in poverty and lowering the impact of poverty on children, but no targets. The Northern Ireland Audit Office found that there was little sustained progress against most of the poverty indicators and reported that a key reason for this was the lack of targets.4 The anti‐poverty expert panel recommended that the next child poverty strategy (there has been a commitment to publish an anti‐poverty strategy with a key focus on children in 2025) sits at the heart of government so that there is better co‐ordination across different departments.

‘The social security support isn’t sufficient enough in Northern Ireland, which is a bad thing. More and more people on universal credit whether working or not are having to use food banks and more and more families are being plummeted into poverty as a result of a system that does not work to sustain families. Families’ basic needs are not being met. People over here are choosing not to put their heating on during the day whilst their children are in school. Heating is now becoming a luxury instead of something that’s essential.

‘My children also avail of means tested free school meals. Only one meal a day is provided by the education authority that is free and if that’s not suitable then you pay a top up fee. My son has additional needs and can only eat certain foods. Before the pandemic the education authority used to cater for children with additional needs but due to severe budget cuts this has now all changed.’

Deirdre, single mother to two children, former teacher, participant in Changing Realities

England

The actions of the Westminster government are particularly crucial for determining families’ experiences of poverty in England, as there are very limited devolved powers. Free school meal provision, outside of London, is the most restrictive of anywhere in the UK. England is also the only part of the UK that does not have a national scheme for uniform costs for low‐income families.

Since the Child Poverty Act was abolished in 2015, there have been no obligations for local authorities to take action on child poverty, although some have done. The Mayor of London has rolled out universal free school meals to all primary schools in London, and other local authorities, such as Bolton Council, have developed child poverty strategies.

Local action to tackle child poverty can make a real difference to children and families, but in the context of large cuts in funding to local authorities and limited control over the policy levers that affect family income, tackling child poverty effectively at a local level can be challenging. Local authorities in England need the back up of an effective UK‐wide cross‐government child poverty strategy, to support these efforts and address some of the key drivers of child poverty in their communities, such as cuts to social security.

‘As a low income family, we have been supported with income based free school meals and as a result have been able to apply for some summer camps during the school holidays. This has been a real blessing as my daughter has additional needs and can become overwhelmed when her daily routine differs in the breaks at school. The school my children go to has no second hand school uniform for sale, no uniform grants and no subsidies for school trips/outings. There have been times where I have had to turn to our local council to access their local welfare assistance scheme, because when I moved I couldn’t afford the cost of the removal van.’

Mollie, mother to two girls, carer and campaigner, participant in Changing Realities

Looking ahead

A cross‐government child poverty strategy for the UK will need to operate in the context of further devolution, which will create opportunities for effective local initiatives to tackle child poverty. However, these will need to be reinforced by effective policies at a UK level, particularly on social security.

The UK strategy must include investment in the social security system. This must start with abolishing the two‐child limit to prevent further rises in child poverty over the coming years, and ending the benefit cap, which pushes children into deep poverty. An increase to child benefit of £20 a week would lift 500,000 children out of poverty. Child benefit is a near‐universal benefit and would both reduce and prevent poverty, as a benefit that is received by families above the threshold for means‐tested benefits.

Other policy areas that are critical to tackling child poverty, and so should be in the strategy, are:

- decent work, pay and progression

- quality, affordable childcare when families need it

- inclusive education

- secure homes for families

- services and support for children and families.

It is clear from the experience in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland that an effective child poverty strategy needs clear leadership, infrastructure across government and ambitious targets to work towards.

A mix of policies at both a Westminster and a devolved government/local level are needed to tackle child poverty in the long term. The forthcoming UK strategy creates a real opportunity to unlock the national policy change that is needed in these different areas, which can then be built on at a devolved and local level.

CPAG is grateful for the funding provided by Oxfam GB to support this work.

Subscribe to CPAG's Poverty Journal

To read the rest of this issue, sign up for an annual subscription