Seven years in Scotland

A new first minister has just taken office in Scotland. Like his predecessor, he has said that his first policy priority will be eradicating child poverty. What progress on child poverty has already been made in Scotland? What lessons can be learned? And what more needs to be done?

‘Give the people who are struggling a bit more money.’

These are the words of a young person from CPAG in Scotland's Cost of the School Day Voice Network, one of four thousand pupils we asked last October to identify the costs that matter most to them and what could help address these. In their answers, many young people prioritised just this: Give the people who are struggling a bit more money.

In the past several years, the Scottish government, with support from across the political spectrum, has made a series of concerted efforts to put ‘a bit more money’ into the pockets of low‐income families – whether through targeted cash support or efforts to improve services and access to employment. The result has been some significant progress on child poverty in Scotland. This has largely been made possible by two things: the devolution of some social security powers to Scotland through the Scotland Act 2016 and statutory targets agreed by all the political parties in the 2017 Child Poverty (Scotland) Act.

What progress has been made?

Increasing income through social security powers

Inadequate income from social security is one of the key drivers of child poverty. The biggest achievement of the past several years in terms of addressing this is Scottish child payment. Beginning in February 2021, Scottish child payment used the power given to top up UK‐wide benefits through the 2016 Scotland Act to provide an additional £10 a week per child under six for families on universal credit (UC) or other qualifying benefit. Now £26.70 a week for eligible children up to age 16,1 Scottish child payment has become a powerful and far‐reaching tool to help the most hard‐pressed families make ends meet. All available estimates suggest that Scottish child payment alone has already lifted between 40,000 and 60,000 children out of poverty.2

While Scottish child payment is the most impactful use of new social security powers, other devolved payments have also been introduced to boost incomes for families in Scotland. These include Best Start foods and Best Start grant (replacing Healthy Start and Sure Start in the UK), with two additional early years and school‐age payments.3 The combined value of benefits provided to low‐income families through Social Security Scotland (SSS) is worth up to £10,000 by the time a child turns six.4

Addressing the other drivers of child poverty

The Scottish government has also recognised the need to address other drivers of poverty, including lack of income through employment and high costs. The Scottish government’s child poverty delivery plan commits to reducing the gender, ethnicity and disability pay and employment gaps that underpin much of the nation’s child poverty. However, it is far from clear that adequate efforts are being made to tackle the structural employment barriers and inequalities that these groups face. Similarly, the plan recognises the role housing costs play in driving children into poverty, yet the latest Scottish Budget saw a substantial cut to affordable housing investment.5

The current 2022‐26 tackling child poverty delivery plan, Best Start, Bright Futures,6 seeks to build on existing progress on both free school meals and funded childcare. Commitments to expand universal free school meals to all primary school pupils will help to reduce stigma and manage costs for low‐income families. Additionally, commitments to further expand the offer of 1,140 hours of funded early learning and childcare to one‐ and two‐year‐olds could, if adequately funded, help reduce costs and improve parents’ access to more, higher‐quality work. But it’s important to mention that, with less than two years remaining of the current delivery plan, there has been little progress in implementing these commitments. There have been delays to the original timeframes for rolling out free school meals to Primary 6 and 7 pupils, and in the latest Budget it is not clear that enough resources have been allocated to fund the expansion of this committed childcare offer.7

Impact on household income

What have these policies meant for families? The combined impact of Scottish child payments, other family benefits and lower childcare costs has been to significantly narrow the gap between family incomes and the cost to bring up a child at a socially acceptable standard of living. Research on the cost of a child in Scotland for CPAG finds that the combined value of these policies can reduce the net cost to low‐income families of bringing up a child by more than one third compared to the rest of the UK.8 Analysis from the Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS) estimates that on the whole, for the poorest 30 per cent of households, Scottish tax and benefit policies mean families with children in Scotland see their incomes boosted by around £2,000 a year compared to those in England and Wales.9

Improved ‘cash first’ crisis support

There has also been progress in Scotland on cash support in a crisis. The Scottish welfare fund (SWF), introduced in 2013 after the abolition of the UK discretionary social fund, provides emergency grants to people in financial crisis. It is a national scheme underpinned by legislation and supported by statutory guidance, administered by local authorities (similar support is still not available in many local authorities in England). In June 2023, Scotland became the first country to release a government plan to reverse the rise of food banks. The government outlined a commitment to prioritise a ‘cash first’ approach that would get more money into people’s pockets through improved access to SWF and other benefits.10 For families and children, this additional cash first support appears to be beginning to work. Analysis by Fraser of Allander Institute for the Trussell Trust, the UK’s largest network of food banks, has found that Scottish child payment has had an impact in reducing food bank use for households with children, particularly in late 2022 to early 2023 after the payment was raised to £25 a week.11 Recent data from the Family Resources Survey also suggests that households with children in Scotland are less likely to have used a food bank than in the UK as a whole.12

Shift to a rights-based approach

The Scottish government’s plan towards ending the need for food banks is part of a wider rights‐based approach to poverty. In the past several years, as well as positive policy interventions like those mentioned above, there has been a broader shift in Scotland towards this human rights approach.

In 2018, the Social Security (Scotland) Act, which was unanimously passed by Parliament, placed the principles of human rights, dignity and poverty reduction at the heart of the social security system – following years of advocacy from the Scottish Campaign on Welfare Reform (now the Scottish Campaign on Rights to Social Security). A charter was also developed by SSS in partnership with people who had lived experience of the social security system. In 2023, almost nine in 10 people surveyed believed they had been treated with dignity, fairness and respect by SSS.12 The latest customer experience survey from the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP), for 2020‐21, does not ask similar questions on dignity, fairness and respect. What is notable is that only 62 per cent of respondents claiming personal independence payment agree the DWP tailored services to their particular personal circumstances.13

Recent advances in human rights legislation in Scotland may also have an impact on how child poverty reduction work is framed in the future.

In January 2024, Scotland became the first devolved nation to incorporate the United Nations (UN) charter on the rights of the child into domestic law, which includes a human right to health, standard of living and social security.14 Scotland also has advanced plans to bring forward a Human Rights Bill in 2024 which will incorporate more than four UN human rights treaties into Scots law. These changes have the potential to improve accountability of public bodies as well as accelerate and strengthen calls to reduce child poverty – but what this will mean in practice remains to be seen.

The Scottish government has also commenced work on the delivery of a Minimum Income Guarantee to ‘provide everyone in Scotland with a minimum acceptable standard of living.’15

Where are we now?

There has been some real and impressive progress on child poverty since the passing of the Child Poverty (Scotland) Act in 2017. However, the reality is that the current suite of policies looks unlikely to be enough to meet the statutory interim 2023–24 child poverty reduction targets, and the Scottish government’s own analysis shows its current policy package will see it fall far short of the final 2030 child poverty reduction targets. In March 2024, official child poverty statistics revealed that 240,000 children (24 per cent of all children) remain locked in poverty in Scotland.16 These statistics, which don’t yet include the full rollout of Scottish child payment and its increase to £25 in November 2022, show child poverty to be broadly stable in Scotland. This is both disappointing and a stark reminder that much more needs to be done to achieve intended progress on child poverty.

In this context, the choices made in the most recent Scottish Budget are particularly frustrating. In the 2024–25 budget, the Scottish government did not raise Scottish child payment to the £30 a week the former first minister Humza Yousaf had said he wanted to see in the previous leadership campaign. Instead, the government announced a council tax freeze which provided little if any benefit for lower‐income families. Had the cost of the council tax freeze been used instead to increase Scottish child payment, it’s estimated that at least a further 10,000 children could have been lifted out of poverty.17 It’s clear that more needs to be done to prioritise Scotland’s commitment to reduce child poverty and use all of the powers at its disposal to do so.

What more needs to be done?

Maximise impact of current policies

First, much more can be done to maximise the impact of Scottish child payment, arguably the most powerful, effective and efficient tool at the Scottish government’s disposal in tackling child poverty. Increasing the payment to the promised £30 a week would go a long way – but there is widespread agreement that a payment of £40 is needed.18 For other devolved benefits, such as Best Start food and Best Start grants, progress must also be protected by ensuring they keep their real‐terms value.

To improve crisis support, action can be taken to ensure the effectiveness of the SWF. Charities, including food banks, have long raised concerns that too many people face barriers accessing support from the fund.1920 To ensure the fund fulfils its purpose, there needs to be increased and sustained investment in its value and administration (as well as enacting the recommendations made in the 2023 SWF action plan).20

The Scottish government also needs to accelerate and expand on commitments made in the tackling child poverty delivery plan. This includes delivering on the commitment to fully roll out free school meals to all Primary 6 and Primary 7 pupils.

And while current investment in early learning and childcare is welcome, this is also not enough. At the very least, resources must be allocated to expand early years and childcare provision as set out in in the programme for government and tackling child poverty delivery plan. Beyond this, a plan is needed to move toward a funded system of 50 hours childcare a week for all children more than six months old, free at the point of use.21

Use devolved powers to go further

As well as protecting the value of policies that have proven to be impactful, more can be done to continue to plug the gaps caused by harmful Westminster policies that push children and families into poverty. For example, Scottish child payment could be used to provide additional payments to families affected by the two‐child limit and young parent penalty (the lower rate of UC for under‐25s).

It is also vital to support families and children with no recourse to public funds within the constraints of the DWP and Home Office, using all possible social security powers and discretionary powers available to local authorities.

It’s already been suggested that Scotland’s devolved tax powers are working to help boost incomes for poorer households.22 However, it should be possible to further reform tax in Scotland to raise the revenue needed to, for example, invest in childcare and remove barriers to employment.23

To further improve the quality of paid work, Scotland could also do more to use its public procurement and public body wage‐setting powers to drive improvements, such as addressing low pay and incentivising payment of the real living wage.

Impact of UK policies

While there are plenty of powerful tools at the Scottish government’s disposal, these face the reality of Westminster policies that are actively pushing children into poverty. From 1998 to 2010, child poverty fell significantly across the UK as a consequence of broad investment, but most significantly through spending on benefits and child tax credits.24 CPAG estimates that the two‐child limit affects 1.5 million children in the UK (80,000 in Scotland), 1.1 million of whom are living in poverty.25 Lifting the two‐child limit would be the single most cost‐effective way to reduce child poverty across the UK and would lift 250,000 children out of poverty, around 15,000 of them in Scotland alone.2627 To truly shift the dial on child poverty, we need all levels of government engaged in addressing the drivers of child poverty – not contributing to them.

What’s next?

Scotland’s new first minister has said that his first policy priority is eradicating child poverty.27 Despite the positive progress made, the current package of policies will not be enough to meet the Scottish government’s own statutory targets. As Scotland moves closer to its 2030 deadline, what lessons from the past few years should John Swinney take on board as he charts the way forward?

The political choices made in Scotland, like the introduction of Scottish child payment, are making a tangible difference to the lives of thousands of families in Scotland. Families such as Nanda’s, a parent and participant in the Changing Realities project,28 who says:

‘The Scottish child payment helps me monthly to make things a bit easier. It is helpful for my children as it’s a small way for me to meet their needs. I find it helps me on some weekends we can spend quality time together and do some cheap activities like the play centre. Even if we don’t have much money, I want them to be happy and have fun.’

Where the wrong choices have been made – such as prioritising an ineffectual council tax freeze over increasing the value of Scottish child payment – the impact is significant. A child who was six years old when the Child Poverty (Scotland) Act was passed will turn 13 this year. For hundreds of thousands of children in poverty, there is no time for delay.

Finally, with a UK general election on the horizon, the most important lesson from progress made on child poverty in Scotland in the past several years is that ending child poverty can be a collective and national mission. It is possible to build cross‐party and cross‐government commitment to reduce child poverty that leads to real change. Poverty has devastating costs for families, communities and the economy (a conservative estimate of lost income due to poverty is around £2.4 billion a year in Scotland).29 Child poverty is everyone’s problem. When progress is made, we all win.

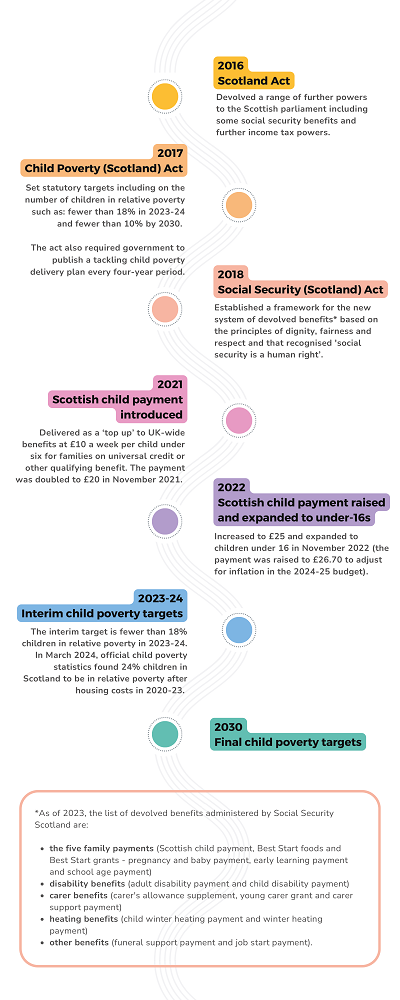

| Date | Event | Details |

|---|---|---|

| 2016 | Scotland Act | Devolved a range of further powers to the Scottish parliament including some social security benefits and further income tax powers. |

| 2017 | Child Poverty (Scotland) Act | Set statutory targets including on the number of children in relative poverty such as: fewer than 18% in 2023-24 and fewer than 10% by 2030. The act also required government to publish a tackling child poverty delivery plan every four-year period. |

| 2018 | Social Security (Scotland) Act | Established a framework for the new system of devolved benefits30 based on the principles of dignity, fairness and respect and that recognised 'social security is a human right'. |

| 2021 | Scottish child payment introduced | Delivered as a 'top up' to UK-wide benefits at £10 a week per child under six for families on universal credit or other qualifying benefit. The payment was doubled to £20 in November 2021. |

| 2022 | Scottish child payment raised and expanded to under 16s | Increased to £25 and expanded to children under 16 in November 2022 (the payment was raised to £26.70 to adjust for inflation in the 2024025 budget). |

| 2023-24 | Interim child poverty targets | The interim target is fewer than 18% children in relative poverty in 2023-24. In March 2024, official child poverty statistics found 24% children in Scotland to be in relative poverty after housing costs in 2020-23. |

| 2030 | Final child poverty targets |

Subscribe to CPAG's Poverty Journal

To read the rest of this issue, sign up for an annual subscription